Revolution at the V&A (p6)

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world” This quote from the nineteen-sixties by Margaret Mead was greeting visitors to the Revolution exhibition, currently at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is an encouraging thought in our times of globalisation, dominated by corporations with turnovers well above many nation state budgets. Was is really possible for a lot of small groups committed to ‘change-the-world-for-the-better’ to divert the path of these tankers steaming ahead in neoliberal waters? Surely, then as now, that would require a great deal of idealism, commitment and staying power.

Many among the visitors had smiles on their faces remembering the scot-free times of their youth in swinging London, hippy America, or ‘remaking-the-world’ Paris. Yet memory is an unreliable witness. Looking back at the revolutionary nineteen sixties, with their flower power, creativity in so many fields, their activists who believed in a better world it is worth pausing for thought about how quickly all their hopes had been thwarted, and how the pendulum had started to swing the other way ever since.

Arab Spring: huge hope, short life. Source: http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/Ideas-and-Movements-behind-the-Arab-Spring.htm

Yes, there was the Arab spring – oh so short lived – with unthinkably traumatic consequences for generations to come. There still are the fringe parties in Greece, Spain, Italy and elsewhere wanting more direct democracy and greater engagement of the citizens in politics. It is important to remember though the equal, if not larger number of movements on the other side promoting xenophobia and exclusion.

The exhibition is a snapshot of 1828 days from 1966 to 1970, focusing on music, fashion, visual and performance arts, besides some political activism and momentous events, the most memorable among them the Vietnam war. It mentions in passing events in Eastern Europe rebelling against Soviet domination. There is little about CND, very active during that time, and its geography is concentrating on London, Paris and California.

According to the curators’ intention the exhibition shows revolutions of identity, ideas, consuming, living, communication, and in the street. Quoting environmentalism, feminism, black power, but also consumerism and neo-liberalism, it claims that the ’68 revolution is still with us.

Like all such movements this one was not homogeneous and sparked controversies at the time, let alone establishment opposition in response to violence infiltrating this initially peaceful ‘revolution’. By their nature such exhibitions are constructed through the eyes of the curators. Having been on the barricades at the time, my fallible recollection is rather different. Living through ‘history of the present’ is bound to be confusing, as one experiences only events in one place and at one time while many other manifestations of contest and counterculture are taking place elsewhere.

Yet, May ’68 was far more than students wanting to have access to each others’ dorms. The sexual revolution facilitated by the contraceptive pill was already a reality. What these years did was to federate the many progressive movements already under way, the claim for gender equality, the fight against racism and segregation, unilateral nuclear disarmament, conscientious objection to the Vietnam war, respect for the environment and rebellion against mindless consumption due to industrial inbuilt redundancy, freedom of expression, human rights, demand for critical education, free flow and sharing of information not only among artists but also among researchers and scientists across the cold war wall, and much more. It was also the time when a new generation demanded to revisit critically what had taken place during the second world war. If anything, youth was more politicised, not just among the educated and academics but also on the factory floor. May ’68 included the belief that youth from all walks of life shared the yearn for a progressive future, although it transpired later that the cultural gap was probably too large to be straddled by idealism alone.

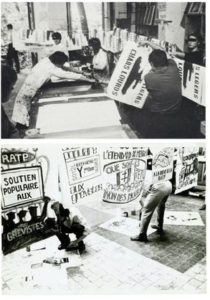

From the point of view of urbanism, the street played a crucial role. Debates between different factions took place in the public realm, as well as fights against police repression, but also the belief that a better future could become reality. The exhibition mentions the Situationists but remains silent about the equally influential conception of the city explored at Nanterre, the university in the ‘red’ belt led by Henri Lefebvre; the occupation of the Sorbonne by the urban researchers who proposed a new approach to understanding and intervening in urban development; or the revolutionary view of the arts by Pierre Francastel shared at the Sorbonne on Saturday afternoons with on open audience, well before John Berger’s ‘ways of seeing’ (1972). Francastel’s sociological approach to the arts was of special interest for those concerned with urbanity as he expressed spatial concerns. To name but a few, painters like Robert Lapoujade (choses vues) and art critic Jean-Louis Ferrier took up May ’68 in their works. These are just examples to illustrate what broad repercussions that ‘revolution’ had, ranging from the creative to the political. Moreover, all that was playing out in the city and its streets.

May 68 Message in the Street. Source: http://cdn06.strandbooks.weblinc.com/images/products/partitioned/3/8/1/0956192831.3.zoom.jpg

Looking back at the belief in a better world during the revolutionary nineteen sixties and how quickly social alternatives had vanished it takes more than optimism to start again. The world has changed enormously since ’68. For one thing small groups can resort to social media to pool their actions. Nevertheless, it is hard to believe in Margaret Mead’s credo that small groups would be able to derail increasingly hegemonic neo-liberalism in our times.