Revolution – Almost But Not Quite

Two aspects came to mind from the conversation between the translator Donald Nicholson-Smith and the art historian Timothy J Clark: one was the challenge of ‘translation’, the other the revival of interest in ’68.

Transposition

The occasion was Nicholson-Smith’s new English translation – ‘The Revolution of Everyday Life’ – of the “Traite de savoir-vivre a l’usage des jeunes generations” by Raoul Vaneigem. They debated the radical ideas, as well as the stylistic merits of the situationists with a full house at the London Review of Books on 26 March 2013.

Both were past members of the British section of ‘Situationist International’, and inspired by the radicalism of Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem. They thought that the failure of ‘Situationist International’ was that its politics of non acceptance did not translate into the Anglo-Saxon world. This remark is relevant to the whole debate about the possibilities and limitations of translating one world into another. While ideas may be universal culture is not. The same applies to language, which is defined by, and defining culture, each with its irreducible core, its uniqueness encapsulated in its own expression of ideas, in its lived existence. The ultimate ‘reserved verbal space’ is poetry, a creative mode of expression unique to each poet. It needs a poet to translate poetry, as did Stephane Mallarme and Edgar Allan Poe who translated each other’s poems. In some ways, both Vaneigem and Debord considered themselves poets and thus free to use or reinvent language. For Vaneigem, “savoir vivre’ means knowing how not to give an inch in the struggle against renunciation”. This is ironic considering that ‘savoir vivre’ in the conventional wisdom of French bourgeoisie meant knowing how to behave in good society, in their society, critiqued by Debord In “The Society of the Spectacle”.

In a similar way, a translator does not only need a good command of the two languages between which he navigates, but also knowledge and experience of their respective cultures, ways of life and, in the case of Nicholson-Smith, situationism and the thinking, position in society and politics of the situationists whom he translated. Or rather, he chose to ‘transpose’ the variegate style and substance of the situationists into his own Anglo-Saxon world of concepts, mores and verbal expression. This re-rendering of the writing of these authors in his own idiom was precisely what more literally translators such as Len Bracken were reproaching him in ‘turning gold into lead’. http://www.lenbracken.com/gold.html

Dia_3 Zazie dans le metro, source: http://milkymoon.cowblog.fr/zazie-dans-le-metro-raymond-queneau-2903538.html

Not only has each language its own structure, syntax, grammar and vocabulary of very different proportions, but it also depends on how it is coded and legitimised. The French Academy decides whether a word is French or not, thus formal French enjoys a strong position. It should not be forgotten though, that during the period of the situationists the subversive and unconventional writing of Louis Ferdinand Celine, Jean Genet, Raymond Queneau, Samuel Beckett, Henri Miller and many others was popular among the activist of ’68 who, moreover, coined their own language among themselves, not to mention the colloquial language of the workers in the car factories on the outskirts of Paris. In this way, the official French language was under attack as a protestation against the disciplinarian state.

Despite their claim to complete refutation of convention, the situationists did not emerge from the big bang. They were influenced by the surrealists, the existentialists, the anarchists and other movements, besides being widely read in the literature of their own bourgeois culture. Nor were they the only ‘revolutionaries’ during the turmoil leading to ’68 which were fomented by students from contradictory political affiliations, conflicting trade unions, an ambiguous communist party and many worker factions.

The ghost of ‘68: the passage of time

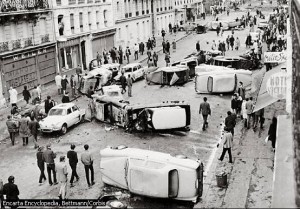

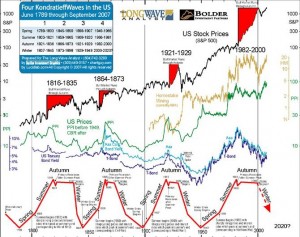

Half a century has passed since them. Notwithstanding that they belonged respectively to Belgian and French culture, Raoul Vaneigem wrote ‘The Revolution of Everyday Life’ and Guy Debord “The Society of the Spectacle” (la society du spectacle) 50 years ago and published them in 1967, just before the pre-revolutionary times of ’68, when non conformist ideas and insubordination of workers culminated in the largest ever general strike in France and the near collapse of the state. However, the situation returned to ‘normal’ as quickly as it has arisen. What is the meaning of these situationist writings now, arguably in a new pre-revolutionary phase of social change, at a new trough of Kondratieff’s waves?

Dia_5 Kondratieff’s waves, source: http://www.financialsense.com/contributors/christopher-quigley/kondratieff-waves-and-the-greater-depression-of-2013-2020

It is interesting to note that frequent references are being made to ’68 – as opposed to any other movement – in debates about the protests of the ‘indignados’ in Spain, ‘Occupy’ in New York, London and sporadically worldwide, the student demonstrations in London in 2010 and the riots in 2011. While the question remains unanswered why ’68 never developed into a full social revolution it was discovered that rebellions at that time were far more widespread than just in Paris, Germany, Italy or the UK and were prolonged by the working class long after the students had returned to their classrooms and de Gaulle had regained power with a landslide. The jury is still out about the popular responses that may yet emerge to the increasingly ruthless raids by the neo-liberals on the nest eggs of unsuspecting wage earners who were saving to take care of their future themselves.

Dia_6 May 68 “beginning of a long struggle” was not to be, source: http://johnnyvoid.wordpress.com/tag/paris-68/