OC 39: Openness and the Fear Industry

Now that the tears over 9/11+10 are drying up, what happens to the ‘fear industry’? Fired by the war on terror it is doing really well. The surveillance and anti-terror industry has mushroomed and is well under way of becoming too big to fail. In the name of war on terror, states have restricted civil liberties, although doubts are being voiced over its pertinence.

1_dia 9/11+10 commemoration source: http://www.funripper.net/911-anniversary-plot/sept-11-anniversary/

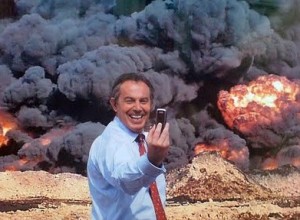

Ex prime minister Tony Blair was quick to justify the war on terror when interviewed on the BBC Today programme on 10 September. He claims that radical Islamic fundamentalism is a widespread ideology stopping at nothing, without envisaging that his own imperialistic righteousness and belief in the universality of western style democracy can be construed as equally fanatical, intransigent and exclusive. In his mind, Britain’s security sanctions his missionary zeal for war on terror, arbitrary selection of ‘the enemy’ guided by self-interest, prosperity through access to resources belonging to others, and clinging onto status of world power.

2_dia Tony Blair in war zone source: http://www.davidicke.com/headlines/36284-why-did-tony-blair-receive-a-heros-welcome-in-kosovo-he-should-have-been-arrested-as-a-war-criminal-

Blair is right in thinking that the war on terror and freedom are not opposites. His reasons though are fallacious. War on terror has not broadened but seriously infringed freedom. This goes for individuals, their greater exposure to surveillance, the restriction of their movements, intrusion into their privacy, even incarceration without being charged or tried, a violation of basic rights of habeas corpus which constitute the core of western values.

Yet, the war on terror does not just affect individuals. It has great repercussions on cities and urban way of life. Besides terrible loss of lives, terror attacks have destroyed urban infrastructure in Madrid and London, and real estate in Bali, Mumbai and New York. The state responded by restricting the public realm. Fences and gates have mushroomed, public rights of way have been waved, gated communities are thriving and becoming the norm for the affluent classes, with the effect that the urban fabric is getting more fragmented and inaccessible. All these measures render more visible the spatial expression of the increasing gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’, exacerbated by domestic austerity which exempts the war on terror.

4_gated community in London source: US:official&channel=np&biw=1338&bih=901&tbm=isch&tbnid=wewrQiOSbFOkbM:

The notion of ‘open city’ is about the freedom of citizens, their wish –some would say their right – to live, work, play and learn in the city unimpaired, without fear. From their point of view, the jury is out on whether the measures legitimised by the war on terror are providing a safer city environment for citizens.

The street has always been, and remains the place where opposition and frustration are manifesting their expression. It is also the place where everyday urban life occurs, the place of public celebration and spectacle. An open city is one where the street is shared between these conflicting claims. Daily incidences illustrate how the ‘fear industry’ is hampering city openness. Writing street conflicts off as social pathology, the mere acts of criminals is not only inaccurate but foolish. Using disproportionate punitive measures will not solve the causes of urban discontent, quite the reverse, they provide fertile ground for claims of social and spatial injustice.

Why is it that nobody asks for a dispassionate, thorough analysis of recent events in the streets of London, which cannot be attributed to the war on terror even by the wildest stretch of imagination. Instead, these urban unrests are written off as caused by the ‘the enemy within’, very quickly identified as the underclass, made up of immigrants, aka Muslims, the other, the foreigner. What does that mean in a city where foreign born births have exceeded indigenous ones for some time, where a third of the population is not ethnic English? How does that opinion tally, if not with multiculturalism, then with the new political fads of localism and the big society?

6_Cosmopolitan London source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2006/aug/30/communities.guardiansocietysupplement

Meanwhile, the open city is paying the price of such ignorance and arrogance.