OC 38: Can Cities Be Too Open?

The limits to openness

During a perfect summer day I was ambling on the boulevards of Paris, enjoying its public realm, open to anyone from anywhere. I did what many people do in open cities, I settled down on a pavement café with a paper and watched the world go by. I came across an in-depth report published by Le Nouvel Observateur [France 30 juin 2011, Dossier, pp 82-104] showing what is happening to the very material fabric of cities and especially the historic gems of the French national heritage.

The report made me think of an article in the Monde Diplomatique [July 2011, Max Rousseau, Le mouvement des immobiles, p10]. Its purpose is to demonstrate how the ever accelerating movement of capital has its counterpart in the ever increasing amount and speed of movements in cities, mainly in the public realm, and how these movements displace people who congregate, stand still, meet and relate to each other: the very essence of city life.

2_dia successful public space where people congregate freely source: http://publicspaceanalysis.wordpress.com/

Ever accelerating movements

Rousseau’s view is that this spiral of acceleration is becoming so vertiginous that it may provoke a reaction against “the city as mobility machine”. He sees resistance in “reclaiming the streets”, temporary autonomous areas [Hakim Bey. TAZ. Zone autonome temorare. L’eclat, Paris 1997], the ‘Citta Slow’ and the ‘slow food’ movements. For him, a significant example of such resistance, reclaiming the public realm and its function as place, not as thoroughfare is the occupation of Puerta del Sol in Madrid, and other central places in other Spanish cities.

3_dia citta slow market in Florence, Italy source: http://weseeweare.wordpress.com/2010/10/09/citta-slow-market-firenze-italy/

Reclaiming urban space

There people protested against the neo-liberal city, against opening the floodgates to consumerism, traffic, and most crucially to real estate speculation. The urban fabric has become pure commodity. It is traded like stocks and shares in the capital markets. It has imploded in Spain in a big way during the financial crisis. This means that the very essence of the material city has been transformed into fictitious speculative capital, totally divorced from its use value which the resistance is now reclaiming.

4_dia Sesena, speculative housing in the Madrid outskirts (authors: Luis Galan Garcia & Daniel Fernandez Pascual} source: http://www.deconcrete.org/2011/03/16/a-road-trip-through-madrids-bubble-challenge/

Inventory

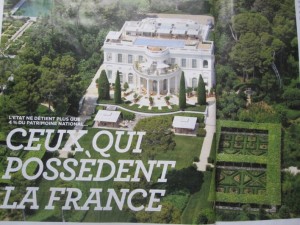

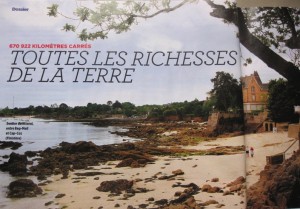

Here is the link with the narrative of the Nouvel Observateur report. It shows how the French architectural heritage, the royal palaces, churches, aristocratic castles and mansions of the rich bourgeoisie, cultural buildings, office blocks or the housing stock, even nature, such as the seashores, forests, vineyards and fields are being inventoried, attributed purely monetary value and capitalised as saleable assets. Nothing seems to escape this potential shopping list, be it immobile or mobile, man-made or natural, owned by the people in the form of state, local state or church property, or in private hands.

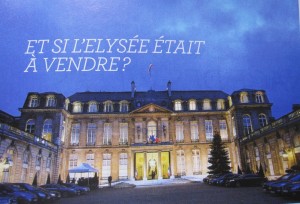

Most of these valuable assets are concentrated in cities. They are open for grabs, monopoli games, kleptomania, worldwide, seriously challenging the meaning of ‘patrimony’. This trend is by no means confined to France. Simply, the Nouvel Observateur report is showing quantitatively the breadth and depth of the disappearance of assets in the public domain, and the processes of divestments. Even the Elysee, the seat of the President of the Republic may not be spared.

In the UK the treasury building has been sold a long time ago and leased back in parts to the government, so why not the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace, the Tower of London? Is this what is meant by the Big Society? And how does it relate to Localism, devolution of decision making or – god forbid – power to the people, control over the places where they live and work, and sharing those where they play and learn?

7_dia Treasury and Foreign Office, London with lots of ‘closed’ spaces http://viewfinder.english-heritage.org.uk/search/detail.aspx?uid=60211

Withering away of the brick and mortar heritage has been going on for some time. Yet, it was never totally comprehensive and nakedly fostered by the state or cities which are now squandering their fixed capital assets to prop up their running costs. Macmillan’s warning of selling the family silver comes to mind, but in contemporary France this includes where the silver was kept, where it was made, possibly where it was mined. The state is divesting itself of buildings with high maintenance costs to the cities, which may well have to sell them when austerity measures start to bite.

8_dia House of Victor Hugo on Guernesey owned by the City of Paris, possible candidate for sale source: JR from Nouvel Observateur

Who are the afficionados of these gems?

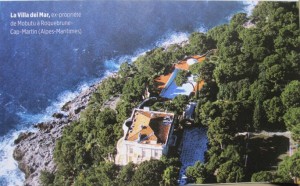

While England is quibbling about curbing use classes, the most prestigious castles, including parts of Versailles, are turned into luxury hotels, the most valuable historic buildings of the city are sold to African dictators, Middle Eastern oil magnats, American institutional investors, Russian oligarchs and, more recently the Chinese.

9_dia Villa Del Mar, Roquebrune, Cap Martin, Alpes Maritimes, owned by Mobutu source: JR from Nouvel Observateur

10_dia Place Vendome, almost entirely owned by foreign protagonists source: JR from Nouvel Observateur

According to INSEE [the French national statistical office] http://www.insee.fr/en/default.asp 3.4%.of the estimated real estate patrimony of France worth 12,115 trillion Euros is owned by the public administration (state, municipalities and national enterprises and financial institutions confounded). True, individuals own 76.5% of the built stock, but this consists mainly of individual dwellings built and privately purchased by the private sector with mortgages, together with often inherited farms, while the patrimony for sale has been financed by society at large.

How open?

These processes reflect almost limitless openness. But to whom, for what purpose? Cosmopolitanism and openness almost universally acclaimed as a necessity for cities to secure their survival and competitiveness. Yet, should such openness be accompanied by unconstrained sales of their material patrimony? Most critically, should this apply also to the public realm which is openly accessible to all?

Selling off the public realm to the highest bidder with no cultural connection to the city means losing control over it and undoubtedly curtailing access to and use of it. This may have far reaching implications as the urban public realm has always been and remains the locus of public interaction and debate. Withdrawing the public realm from the public good would infringe demonstrations and protests and could become a challenge for the future of democracy and the vitality of cities as its natural setting.

12_dia Resistance movement on Puerta del Sol, Madrid source: http://www.friendlyrentals.com/blog/en/madrid/suggestions/stadiummuseumplazapalace-posts-33-4_1184.htm