Open Cities 25 “IABR Open City”

“Open City” seems to have entered public consciousness as this name tag has been adopted for many diverse purposes.

One example is the UK opencity website which invites everyone to chat about their city, initiate exchanges, participate in discussion forums, look for jobs, accommodation as well as any other goods, communicate among students or obtain tourism tips.

Open City: Designing Coexistence

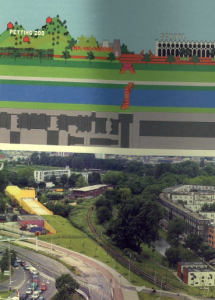

Open City has also be adopted by the International Architecture Biennale in Rotterdam (IABR) for its event on Designing Coexistence in 2009 for its fourth edition. The proceedings Open City, Designing Coexistence edited by Tim Rieniets, Jennifer Sigler and Kees Christiaanse was published by SUN (Utgeverij, Martin de Vietter Amsterdam, ISBN 9789085067832 €42.50) with the support of ETH (Eidgenoessische Technische Hochschule, Zuerich Switzerland. Part One, Dimensions, includes essays by urban thinkers such as Saskia Sassen, Ash Main, Dieter Laeple, Peter Sloterdijk, Stephen Graham and many others. Part Two, Situations, documents commissioned projects in depth aimed at situations where the open city is most challenged. All pictures are from the book.

The Biennale was founded in 2001. Its purpose is to find out what contributions architects and urban designers can make to a sustainable quality of the urban environment by fostering diversity, vitality and viability, and to achieve social, cultural and mutually beneficial coexistence in cities through engagement in the urban process in the pursuit of an Open City.

Previous Biennales focused on mobility (a room with a view), the flood and power: producing the contemporary city. For references to the proceedings see:

http://www.iabr.nl/NL/activiteiten/boeken/index.php

The venues of the fourth biennale were not confined to Rotterdam and many cities worldwide – Sao Paolo, New York, Amman, Istanbul among them – contributed exhibitions, art installations towards the Urban Century Project. They encompassed the informal city if the 21st century (Sao Paolo) exhibited in Berlin; Open City: refuge urbanism in Amman, Jordan; Princen’s refuge, five cities presented in New York; an effort to bridge the urban divide illustrated by Paraisopolis in Sao Paolo by SEHAB, ETH and IABR; and art, research and proposals collated in a refuge exhibition in Istanbul to show bottom up solutions for refuges in Istanbul, Beirut, Amman, Cairo and Dubai.

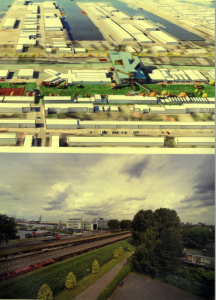

In Rotterdam, where 1200 visitors attended the opening, projects putting social issues of tomorrows cities on the map were selected to illustrate innovative forms of cooperation in cross media form (radio, TV and high resolution web downloads). 60’000 visitors of which one third from abroad had the choice between four exhibitions, 200 events and five documentaries. Local residents were invited to participate in interventions, many of them acted out in the local public realm.

The large exhibition space enabled a broad variety of views to be expressed in terms of models, multi-media presentations, happenings and debates. All somewhat disorganised, spontaneous, disorderly, reflecting Jane Jacobs declaration ‘if density and diversity give life, the life they breed is disorderly’. She was the one who coined the phrase open city and her views that the radical planner is to champion dissonance were projected centre stage.

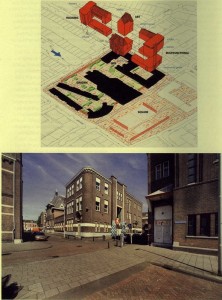

The biennale was not without its critics, but then any innovation will be challenged by those who hand on to traditional values. Among the very rich pickings it is worth singling out the project led by Crimson Architectural Historians which symbolised well the intention of the Biennale. It was called ‘Maakbaarheid’, a Dutch expression which was coined in the sixties and seventies when Dutch urban policy aimed at bottom up emancipation to spead wealth knowledge and power. They were creating Maakbare Samenleving (makeable society), materialised in the open city, an integration machine encouraging diverse communities to establish dynamic relationship to create ‘urbanity’.

‘Transposed into post global crisis society which discredits public planning, Maakbaarkeit’ – often equated with paternalistic social engineering – takes on a new meaning and generates innovative design approaches more in tune with city openness. This is particularly relevant in a city like Rotterdam, a port with a large immigrant population.