Open Cities 9 Openness Latin American Style

Open Cities 9

Openness Latin American Style

‘A City of One’s Own’ (blurring the boundaries between private and public. 2009. Sophie Body-Gendrot, Jacques Carre, Romain Garbaye, editors. Ashgate) is a fascinating collection of historical papers, defying the idea that all our ills are of our time. It addresses the notion of openness from various points of view, planning, housing, security, health, education and citizenship. The section on security encompasses self-defence in neighbourhoods and focuses on gates in communities. The latter article is exploring generic patters of gated communities in suburban landscapes. It refers their origin back to the United States but also to Latin America, arguably for different reasons. In neither of them do the wealthier people wish to live in mixed communities and use enclosure deliberately, thereby reinforcing the social paranoia of secured lifestyles.

Enclose process in Guadalajara

Dia 1 Guadalajara urban regeneration of the city centre which remains public realm

I wish to reflect on my experience of community gating during my recent trip to Guadalajara, Mexico, where I presented a paper at a congress on the future of the metropolis (http://www.reinventarlametropoli.org (proceedings to be published shortly) which has many lessons for the Open Cities research.

Dia 2 Chapala Gates to the transformed railway station

The generic urban design in the Jalisco State in Mexico is not gated. The use of gates has been introduced in response to, or by outside influxes. One example is the disaffected railway station which foreigners who have acquired second homes in Jalisco have rescued from destruction when the railway was abolished in that region. They turned it into a museum of local arts and crafts and reinstated the spaces left behind from abandoned railtracks into a lush garden which they surrounded with a fence and gates, albeit transparent and often open to the public.

Up till now, even in more affluent areas, such as Chapala on the largest lake of Mexico, private houses are set back into their gardens but they remain visible, not hidden behind high walls, and the streets are connected with alleyways and open court yards. Soft boundaries between private and public space are formed by exuberant vegetation which extends into the public realm. Similarly, contrary to many Latin American cities, the poorest areas of informal settlements are not gated off by those who have become their involuntary neighbours by moving out of the city centre.

Dia 3 Soft transition between public, semi-public and private urban space

Slow and silent enclosure

However, in such idyllic areas the high influx of wealthy people from northern climes who purchase second homes, stay for increasingly longer periods, and often end up by settling there, have attracted burglars. As a consequence, the indigenous population is starting to enclose their properties as well and to install remote access surveillance. This process is transforming these spontaneously cohesive and open neighbourhoods into gated communities, gradually excluding whole neighbourhoods from the publicly accessible urban fabric.

Dia 4 Transition between public and private realm

Dia 5 Openness between private and semi-private realm soon to be gated

What effects will that process have on relations between neighbours, old and new, and on the connection between these neighbourhoods whose enclosures are rapidly expanding and the rest of the small towns of which they (ought to…) form a part?

Ex-ante enclosure

Dia 5 New large scale modern gated community in the suburbs of Guadalajara

Guadalajara, the second city of Mexico, is growing very fast due to natural demographic growth and in-migration. It sprawls chaotically into the delicate ecological system surrounding it. Whole new neighbourhoods with gates and janitors are produced on the outskirts by speculative developers. The same happens with informal settlements, a euphemism for poor people who take over land wherever they can to erect precarious shelters. None of these, together with large areas occupied by logistics are integrated in a network of connections with the city centre and even less with each other. Thus the urban fabric becomes increasingly fragmented and segregated with known social consequences in abeyance.

Dia 6 Chaotic urban sprawl in Guadalajara

These trends are occurring also in Europe, perhaps to a lesser degree, with some more planning control, but the fact is that often public intervention limps behind the dynamic of the development process, producing socio-economic cleavages which, with some time lag, become the headache of the public sector, local and ultimately national. The Open Cities programme is addressing some of the causes and remedies of such adverse fragmentation, but the question is how to remedy the real world, cities which have been built to a large extent?

The next ‘post’ presents a remarkable example of how such change from within is possible, how it has been carried out on the ground, with very little financial means but by mobilising indigenous resources, in particular the inhabitants of these deficient urban areas, thus tangibly lowering social ills, such as crime rates, creating conditions for a better quality of life for the most deprived ones, and gradually reducing conflict between factions in the future.

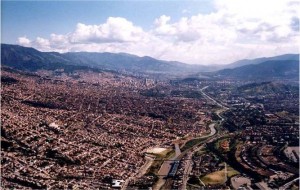

Dia 7 Medellin” new inclusion – new opennes

End.