Open Cities 4 Openness and Closure

Open Cities 4

Openness and Closure

Welcome to open cities

Bright sunshine, holiday time. Many of us plan to take off somewhere to the beach, the mountains, the countryside. Yet, many city dwellers choose to visit other cities. They enjoy to displace themselves for a short while, physically and mentally, to experience another place, immerse themselves into another culture. Open cities are easy for such outsiders to enter, to discover and explore, to compare with their own cities, then to return home, enriched by their encounter with different customs, different people.

Dia 2 Escape from city to sea

Dia 3 Escape from city to mountains

Open streets with cafes, squares with free events, shady parks for a rest invite visitors to join in, to share the space, to share what the city has to offer.

Dia 1 Urban Public Realm

Maybe openness of cities is about sharing with others. Yet, how do those experience cities who find themselves there not so much out of their own free will, but out of necessity? The immigrants, the refugees, the asylum seekers, those who become the minorities in their cities of adoption? They too encounter first and foremost the streets, the squares, the parks. They may feel less welcome though. They may fear that these cities are not really open to them. They may end up experiencing a closed city, one which locks them up, which refuses to share with them and may deport them.

Dia 4 Urban park

Dia 5 Parks for all

Cities are unwelcoming to some

The closure of the reception facilities for migrants in Sangatte on the Channel has not prevented those who were there from staying, nor new ones from coming. Without shelter, they are again roaming the the streets, the squares, the parks which the locals are not willing to share with them. Is Sangatte a closed city? Or at least closed to some while not to others? It is in the limelight again, although the migrants do not want to stay there, they want to move to Britain, but Britain is closed to them as well. Le Pen’s daughter, a candidate for France’s nationalistic right wing party finds favour in that area.

Dia 6 Refugees in Sangatte

About scale and time

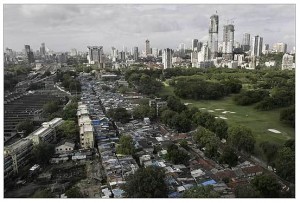

Sangatte is a very small place, although it has the culture of a port, a place with continuous throughput. Perhaps such a small city is not able to absorb so much unlikelihood. But what about larger cities, those who are made up of many minorities, those which had been open to waves of in-migrants over centuries, where more of their descendents are born than of those who had lived there longer? Conventional wisdom states that the diversity of peoples in such cities is constituting their strength, their creative dynamic. What about the tensions between the newcomers and those who consider themselves the more ‘rightful’ owners of these cities? What about the conflicts between the minorities themselves? What openness can reconcile these differences?

Dia 7 Urban housing segregation

Perhaps it is not just a matter of scale, but of time as well, the relative way groups refer to historic time to assert their legitimate ownership of place. Why does it seem impossible to find a solution for diverse groups to live alongside each other in cities without aggression? Why do sectarian acts reoccur despite endless efforts of reconciliation? Why do the people in Belfast now turn against the Romanians, or in fact the Gypsies? Why does it seem so impossible even in cities, the alleged melting pots of cultures, the places of tolerance and mutual respect, to establish if not integration then at least peaceful cohabitation between diverse groups?

Dia 8 Belfast urban wall

About closure

Why do cities surround themselves with walls time and again? Why do they build walls even within, between quarters inhabited by different groups? Physical walls are the most visible manifestation of segregation, but there are many other barriers, less obvious but equally real. Each city maintains separations between groups to varying degrees. Some minorities – meaning ‘worth less’ – are always excluded from the better off, the more powerful, from those who consider the city more rightfully theirs. Can the notion of open city reconcile these social tensions? Can such openness be measured? If it is found wanting, can concrete actions be derived from such measures? If so, what would be the instruments? Who would be in charge of change? With what legitimacy? Implied in this strategy is intrinsic value of openness.

Dia 9 Urban confrontation

The fact that there is closure, that there are barriers confirms that there is no consensus about the worth of open cities. Just imagine a world which venerates closed cities, where barriers are legitimate, desirable even. It is already among us: the ‘gated communities’, the shopping malls riddled with surveillance, the permanently walled airports, the railway stations locked after the last train, streets with public rights of way increasingly absconded by private developers, 24/7 CCTV throughout the public realm. Such physical closeness may simply reflect the wishes of those who feel more comfortable with segregation which enables them to avoid the other.

Dia 10 Urban surveillance

Are open cities only possible if they are wanted by its inhabitants? If society needs open cities for its own survival, how can it win the hearts and minds of its individual members to approve that the cities in which they wish to feel free and safe should be open to others?

Dia 11 Urban market in India

End.