Open Cities 2 Built Environment Perspective

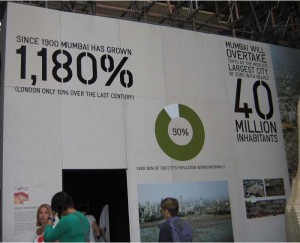

Relentless growth of cities

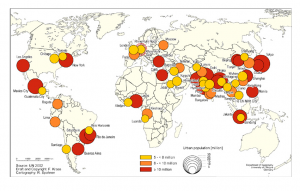

More than half the world’s population is living in cities at present. This is expected to increase to three quarters before this century comes to a close. In this process cities are attracting people from all walks of life.

Dia 1 Largest cities in the world UN statistics

How migration affects cities and their existing population is of prime importance, not only for the future of their economies, but also for the quality of their environment and their social relations. The continuous shift from rural to urban living is well documented. The 10th International Biennale of Architecture in Venice in 2006, and subsequently the 2007 exhibition on cities at the Tate Modern in London gave a comprehensive overview of the growing importance of cities worldwide.

|

|

Competitive advantages of cities

Equally well documented is the role of cities, their location and quality of the built environment, their culture and current position in the economic rank order in attracting and retaining coveted, highly skilled people from all over the world. There exists hardly a city which is not seeking inward investment in its pursuit of becoming a knowledge economy. A quick browse through city websites shows remarkable uniformity of purpose. When competing for a place in the globalising world, cities tend to focus on their current position in the economic rank order and put their energy into improving it.

Dia 3 High flyiers qualified human capital attracted to cities

More recently cities have shifted their efforts from attracting capital to securing human resources. A highly skilled workforce is recognised as an increasingly crucial component of innovation-driven economic growth. City marketing departments started to highlight soft aspects. They tend to highlight their rich culture, their successful history and their social stability. Without subscribing to physical determinism, cities realised that their location and quality of the built environment play an important role in attracting and retaining coveted, highly educated people from all over the world, thus they started to praise their physical assets as well.

What openness?

‘Openness’ ranks high among the advantages which cities present to the outside world when they endeavour to boost their ‘success’. ‘Openness’ commands increasing significance in competing for new lifeblood, in bringing in and harnessing first and second generation immigrants and in incorporating them into other drivers which foster success of cities: the purpose of the UrbAct Open Cities project.

The way cities are translating ‘openness’ varies widely. Some understand it as providing spaces which enable all those who live, work, play or visit the city to share them freely. Schools are a privileged place for social interaction and understanding.

Dia 4 schools are privileged places for multicultural cohabitation

Dia 5 Parallel lives Spontaneous quarters in the shadow of gated communities

Other cities, and in particular those where there exists a wide gap between rich and poor, are opting for spaces which enable specific groups of people to live in secluded places, although they have to share some of the public realm when moving about the city.

Dia 6 Multicultural London East End

Dia 7 City open to cultures

In many open multi-cultural cities groups with similar cultural, ethnic and religious backgrounds tend to concentrate freely in areas of their choice. There are many reasons for that, not least kinship connections, shared language and customs, mutual support based on cultural ties. Below are scenes which illustrate the diverse patchwork of London’s open society.

Dia 8 Cultural diversity in London

Breughel’s Babel Tower the ultimate form of multiculture

These examples raise two questions:

How much do cities evolve spontaneously, with people adapting to each other, adjusting to the urban environment and transforming it to suit their ways of life?

How much are cities and their leaders able to equip their cities to cope with new challenges and to benefit from constant changes?

What characterises open cities is their ability to absorb new forces, ideas and peoples. What and how are spatial policies securing the openness of cities requires further exploration in future posts?

End.