Open Cities 10 Opening up Medellin

Open Cities 10

Opening up Medellin

What has transformed the crime capital of the world into a place of hope and expectation?

Until recently, Medellin, the second city of Colombia in Latin America was the antithesis of an open city. No go areas and gun homocides were the highest in the world.

Dia 1 Youth gun culture in Medellin Colombia

Curbing crime

It took a determined mayor, Sergio Fajardo Valderama, elected in 2003 as an independent until 2008 and now a presidential hopeful, to turn blight into beauty.

Dia 2 The mayor Sergio Fajardo Valdemara (2004-2008) turned the city round

[Interview YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bekm5Y42384 with Sergio Fajardo in Spanish.]

Fajardo managed to transform Medellin from a place of squalor and despair into a liveable open city. He resorted to architects and urbanists, many of them Colombian (Rogelia Salmona, Giancarlo Mazzanti who designed the Parque Biblioteca Espana, Alejandro Echeverri who was responsible for the spatial development strategy, Sergio Gomez for the Botanial Garden), to realise “our most beautiful buildings in our poorest areas”.

Dia 3 Medellin neighbourhood library adn park designed by Giancarlo Mazzani

Instead of reaching for the bulldozers to flatten the many slums of Medellin, as is still customary in many cities in Latin America, Africa and Asia, the mayor built on the tenuous peace imposed by the paramilitary drug traffickers who had outfought their rivals. One statistic confirms the success of these efforts: the city of some 2 million inhabitants reduced its homicides from 381 per 100,000 population in 1991 to 26 in 2008 following the mayor’s credo that “new social opportunities arise from the reduction of every act of violence”.

Learning is key to change

Dia 4 Neighbourhood school

In his view, a city which attempts to fit the 21st century, must make education one of its main challenges. Educating, training and helping young people to acquire skills, providing the poorest with micro-loans and, most visibly, transforming their living environment into a desirable place was possible by involving them actively in the change of their own destinies.

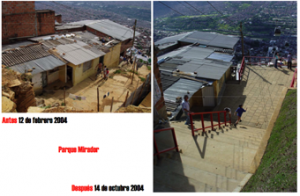

Dia before and after, self-improvement with municipal assistance

His strategy was to begin in the most deprived areas, gain the trust of the poorest with the lowest chances of succeeding in life. Santo Domingo Savio which houses some 170,000 people was the starting point of the regeneration of Medellin from where it has spread elsewhere. Places for learning, schools, a library were deliberately designed as landmarks to signal a brighter future. Parks (of Wishes, of Bare Feet), internet facilities, an art gallery and a day care centre form part of the public realm open to all, together with new connections to the city at large. Converting dilapidated spaces into places where people can meet without fear and the very young population can play triggered improvements to the precarious abodes.

Dia 6 Botanical Garde designed by Sergio Gomez

Beauty to Signify Openness

Openness and, most importantly, beauty was brought to these areas, for which the inhabitants started to feel civic pride.

The locals participated actively in these transformations. Youngsters and the unemployed were given the opportunity to learn building trades. Not only were they able to improve their own abodes, but their skills provided them with jobs and a new lifestyle. In-fills of new housing with better facilities and utilities were gradually added to these areas. The hilly topography segregated the neighbourhoods from each other and it was important to relieve them from their isolation, social as well as physical. Bridges were built across the valleys to create links between the informal settlements. A cable car system connects them with the city centre which had also been given a major facelift.

Dia 7 Bridges link the hills of informal housing

Dia 8 Cable cars link the informal neighbourhoods with regenerated city centre

This enables residents to intermingle anywhere regardless of their social or economic circumstances. The new buildings were deliberately contemporary, using good quality materials. Many spaces were transformed into green areas where even food was being grown. Public art, the Museum of Fernando Botero who was born in Medellin and colourful lighting of the public buildings form part of these changes for a more enjoyable life.

Dia 9 ParqueExplora interactive museum designed by Alejandro Echeverri, director of urban regenerati

Spreading the merits of openness

The innovative changes which have rejuvenated Medellin in such a short time are attracting people from many parts of the world to get inspired by the Medellin experience. Similar initiatives have been undertaken in Bogota and other Latin American cities which suffer acutely from deprivation and lawlessness and were closed onto themselves. Hopefully the current mayor, Alonso Salazar, is able to sustain these efforts despite the tremendous impacts on Medellin of the global recession, unfavourable tariffs and competition from China with its local economy.

Yet the stunning example of Medellin could humble many of us and we could transpose some lessons to our latitudes where we are also dogged with child poverty, social polarisation and spatial segregation, albeit from a higher level of material comfort and relative safety.

End.