Open Cities 20 Redressing Asymmetry

The reason why ‘Open Cities’ is an object of debate is that many urban dwellers are questioning its reality. One way of reaching a judgement is to objectivise ‘openness’ of cities. Another is resistance to asymmetry of uninhibited access to the city. The former is pursued by the British Council which is supporting the development of a metric, an objective measure of ‘open cities’ made up of key factors, components and indicators which will lead to an index, a kitemark and benchmarking. [British Council (Greg Clark). 2010. Understanding Open Cities. British Council]. An example of the latter is TINAG – This Is Not a Gateway – a NGO coordinating and facilitating self generated actions of those working on cities outside the establishment.

TINAG – This Is Not a Gateway

Initiated in the East End of London by young protagonists of cities, TINAG provides the setting for interdisciplinary exchange and active citizen participation.

http://thisisnotagateway,squarespace.com/tinag-background

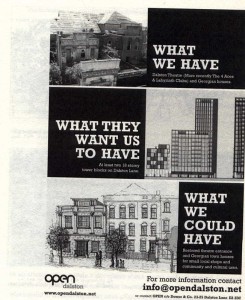

Its instruments are salons, annual festivals, publications, an archive and a library. Its third festival to be held in October 2010 concentrates on “New futures for the financial district of London”. Located in the poor shadow of the wealthiest part of London World City, TINAG had started its festivals in Dalston in the East End, mobilising 97 contributors – urbanists, artists, local activists, writers, historians, locals, visitors – to organise forty events attended by some 400 participants. In 2009, also in the East End, it focused on “regeneration and the public realm”, the latter very much a key ingredient of ‘Open Cities’. The salons generate in depth discussions introduced by invited speakers.

Critical Cities

An ambitious project of TINAG’s is to convert the proceedings of its festivals into a book series. Volume 1, “Critical Cities, Ideas, Knowledge and Agitation” edited by Deepa Naik and Trenton Oldfield, was published in 2009 by Myrdle Court Press.

Ricky Burdett from the London School of Economics provided the introductory thoughts in ‘City Thinking for City Building’ to this collection in which people from very different walks of life express their views in words, drawings, photographs, documentaries or debates on cities and how they are being used. Together they illustrate both urban openness and its deficiencies. ‘Open Dalston’ invited everyone to the debate. Urban motorways carved through Dubai’s landscape are segregating space.

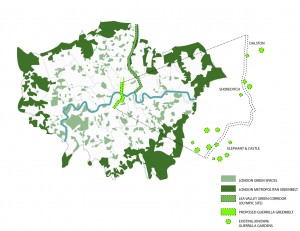

Colonising redundant spaces with plants is a DIY way of providing green connections to the benefit of the city and citizens, as opposed to the closeness of the Olympic site.

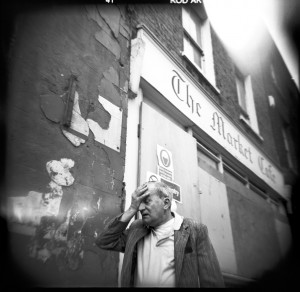

Many articles give insights into the diverse ways of life which cohabitate closely in East London.

Even the presence of vermin is addressed.

Salons

At salons, debates focus on specific themes. The latest example is a gathering during an open night at the Tate Britain where invited activists showed how they refuse to ‘accept their place’.

Dia 7 TINAG Salon at Tate Britain, resistance and spatial reformers, refusing to accept one’s place, photo Judith Ryser

Most of them were East End born and stayed there to improve their lot within their own world. Some found answers in the history of this extremely cosmopolitan area of London with waves upon waves of immigration, as well as out-migration diffusing more established minorities throughout London. Some where staying to fight for better living conditions. Others actively penetrate the power bases beyond their border of poverty to influence them, better still to obtain a piece of the action. Artists use their inside knowledge to expose the lack of openness in their work to a wider audience beyond the East End. There were also visitors from abroad who compared their activism with those of local Londoners. They all contributed to DIY urbanism as a popular means of change.

TINAG is collating all the knowledge and know how from these exchanges in its open library and archive, accessible through its website. Qualitative and interactive initiatives like TINAG contrast with statistical approaches which aim to quantify openness, although this concept does not lend itself easily to such a treatment. It may stand a better chance of being captured in this fuzzy, diverse, borderless environment in which openness may yet evolve into a perhaps more intuitive understanding shared by all.

TINAG’s genuine act of openness presents a challenge to London’s self propaganda, a contribution to be reckoned with by those who endeavour to make London a genuinely more Open City.